Yo!: Enriching Emotional Quality of Single-Button Messengers through Kinetic Typography

Minhwan Kim, Kyungah Choi, Hyeon-Jeong Suk

Daejeon, Republic of Korea

{minhwan.kim, cka0116, color}@kaist.ac.kr

Abstract

This study aims to investigate the effects of kinetic typography elements in single-button messengers to enrich the conveyance of emotional quality. Two complementary studies were conducted: First, a paired user workshop was conducted through which eight macro animation types were extracted to facilitate the evaluation in a subsequent experiment. Second, an empirical study was conducted to explore the effects of kinetic typographical elements, namely animation type, speed, and dynamics, on conveying particular emotions. The study is expected to act as a good stepping stone for further developing single-button messengers as an alternative messaging tool with unique communicational aspects.Introduction

The maturing of technology has led to the relocation of a significant part of interpersonal interaction as instant messaging [9]. It is worthy of close attention that mediated communication tools have shifted from computers and cell phones to smart devices, such as smartphones and smartwatches. Such environmental change has allowed the advent of new ways of communication, and single-button messaging has expanded the possibilities for communication by drastically reducing them. The single- button messenger is an emerging communication application (app) for mobile devices that allows users to exchange limited texts or signals with a single tap. The ‘Yo’ app is a representative single-button messenger that does nothing but send a one-word message, ‘Yo,’ to other users, as shown in Figure 1. The single-button messenger has rapidly become useful as an alternative messenger as we head into the future of wearable devices [2], and a number of similar applications have been subsequently released, such as ‘Hodor,’ ‘Aiyo,’ ‘Dingbel,’ ‘Lo,’ and so forth.

Figure 1. Screenshots of a single-button messenger 'yo.'

However, the single-button messaging application is lacking in a communicational aspect due to its simple functionality. What if users want to say something else? Such questions have led users to use this messenger for a limited purpose, such as an eye-catching notification. Nevertheless, we believe in the potential of this new messaging service, and studies need to be conducted to explore new ways of communication using single-button messaging. In this study, we attempt to embed kinetic typography in single-button messengers.Kinetic Typography

Kinetic typography is defined as text that changes in color, size, or position over time [3]. It easily catches the user’s attention and emphasizes the original meaning of the word. It has been used as an alternative solution to deliver emotional quality in text-based communication, and there have been many attempts to embed kinetic typography in instant messengers [1,4,6]. Lee et al. [7] asserted that pre- designed kinetic typography can convey specific emotions. More recently, Gaylord et al. [5] showed that animated text can add more nuanced communication cues of intonation and body motion. However, those studies have mainly focused on empirical evidence of the influence of different animation types, while they have not yet specified the effects of other elements. Furthermore, earlier studies were conducted in computer-based simulated messengers, and the animation stimuli were pre-designed by experts. In this regard, we conducted a series of two complementary studies on the influence of kinetic typography elements in single-button messengers for mobile devices. First, through a user-participated workshop, we extracted eight types of macro animation for mobile devices. Based on the results, the following study was conducted to investigate the effects of kinetic typographical elements, including animation type, speed, and dynamics, on conveying particular emotions. Lastly, we suggested new ways of using single-button messengers with design implications.preliminary study

procedure

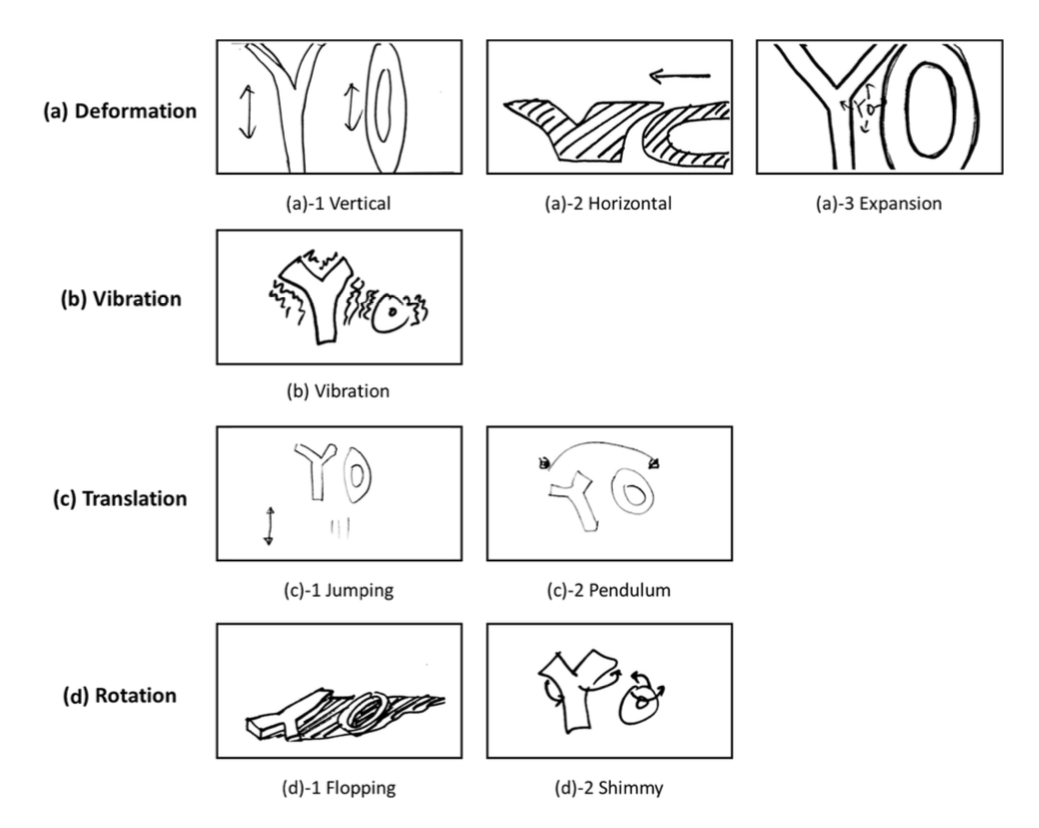

The preliminary study aims to extract user-driven macro animations for mobile devices. We recruited four pairs of users for the workshop. A total of eight college students made up of five males and three females participated. Among the participants, two pairs were in a relationship, and the rest were intimate with each other. Participants sat opposite each other and were asked to express six basic emotions, such as happiness, sadness, anger, fear, surprise, and disappointment [10], using tangible letters ‘Y’ and ‘o’ in the dummy smartphone screen, as illustrated in Figure 2. Two letter sets had different textures: silicone for expressing elastic motion and an acrylic plate for expressing rigid motion. During the workshop, participants were allowed to talk freely and encouraged to give feedback to their partner’s animation. The animations designed for each emotion were archived as thumbnails in a sketched form. Ice-breaking exercises were given prior to the workshop, and five minutes were given to each of the six emotions. Including a ten-minute user interview, each workshop took approximately 50 minutes.

Figure 2. Settings of the user-participated workshop.

Results and Discussion

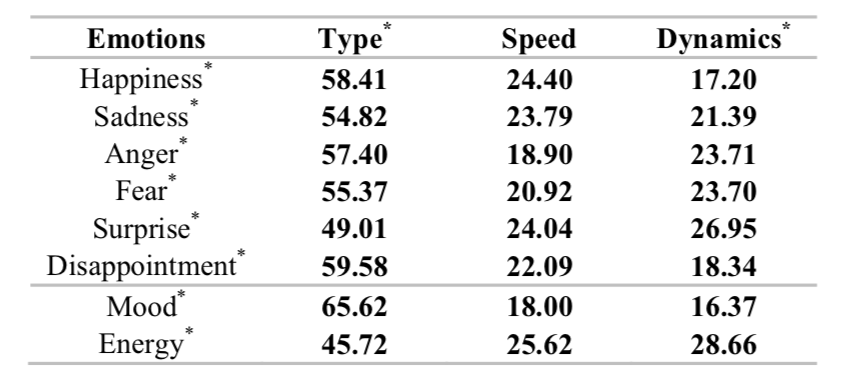

Fifty animations were designed from the user-participated workshop. However, animations with a morphological alphabet that was specific to ‘Y’ and ‘o’ were eliminated. As a result, eight types of macro animations were extracted and were given appropriate names, as shown in Figure 3. Eight animation types were then classified into four groups: The first group is composed of animations with deformation of the original text in three different stretching directions (see Figure 3(a)). The second group consists of vibrating animation (see Figure 3(b)). The third group is composed of animations with a translation in two different motion paths (see Figure 3(c)). Finally, the last group consists of rotating animations in two different rotation axes (see Figure 3(d)). Despite the different participants involved, interestingly, several animations were replicated. For example, ‘flopping’ animation type was repeatedly used to express disappointment. The ‘jumping’ animation type was frequently used to express happiness. This implies that there are stereotypes of animation that are strongly tied to specific emotions. On the other hand, some animation types were controversial in use among participants. For instance, some participants stretched the text vertically to express an angry emotion, while other participants used it to express a joyous feeling. For a joyous feeling, however, a gentle touch was added. This triggered our motivation to investigate the interaction effect jointly caused by more than one kinetic attribute.

Figure 3. Eight types of macro animations extracted from the preliminary study.

Main Study

The main study aims to investigate the role of kinetic typographical elements—animation type, speed, and dynamics—on enriching emotional quality. In particular, we attempted to identify both the main effects and interaction effects among the kinetic elements. In addition, we intended to propose a set of prescriptive rules for the use of kinetic typography, which in turn can be designed as an ‘emotion presets’ in the messenger interface.Procedure

Three kinetic typographical elements were explored in the empirical study: animation type, speed, and dynamics. First, eight macro animation types derived in the preliminary study were adopted as the level of animation type. Second, three levels were defined for speed: ‘slow,’ ‘moderate,’ and ‘fast,’ according to the play time of the animation. The ‘slow’ level had five times longer playtime than the ‘fast’ level, where each level was designed in an equidistant interval. Lastly, the dynamics were divided into three different levels to explore the activeness of animations. For animation types with deformation (Figure 3(a)) or translation (Figure 3(c)), the level of the dynamic is defined by the space covered by the text. On the other hand, for animation types with vibration (Figure 3(b)) or rotation (Figure 3(d)), the levels were defined with the motion range, such as its rotation angle. In order to reduce the number of stimuli, while minimizing the loss of measuring the effect, we adopted an orthogonal design. As a result, 31 profiles, including four holdout profile cards, were composed out of all 72 (8 × 3 × 3) combinations. Including a text without any effects, a total of 32 animated texts were designed and created in Adobe After Effects CS6, which are available at https://vimeo.com/152108052. A total of 20 subjects consisting of eleven males and nine females participated, and their age ranged from 21 to 32 (M = 26.33, SD = 5.67). The animation sets were displayed on a smartphone (iPhone 6s) in order to simulate an instant messaging application in smart mobile devices. Participants were asked to assess six emotional qualities of the 31 animated texts using a seven-point Likert scale. In addition, the responses were recorded in the Affect Grid [8].Results and Discussion

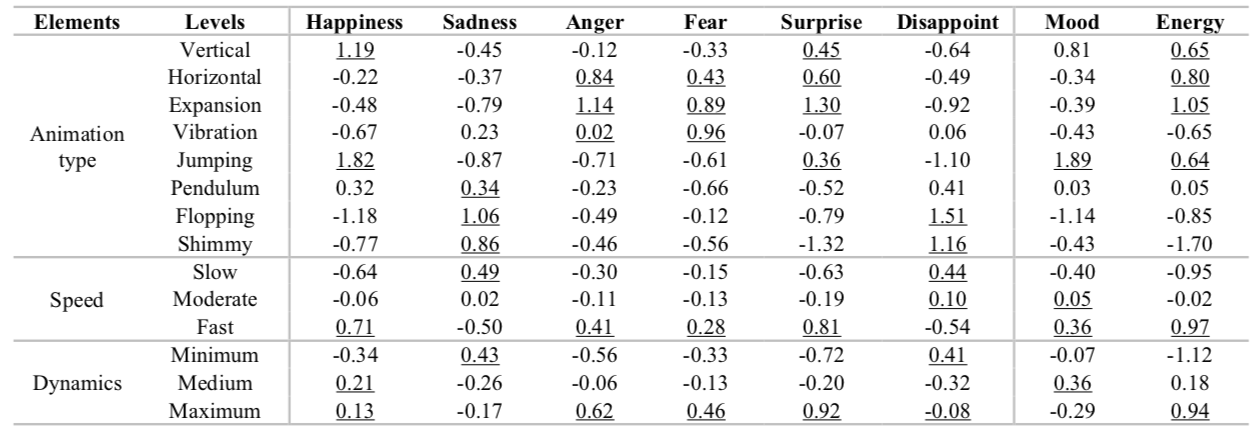

We performed conjoint analysis to identify the elements that have a dominant effect, as shown in Table 1. The relative importance was extracted for each of the 20 participants to perform repeated measures ANOVA. The result indicated that ‘animation type’ plays the most important role in conveying emotions across eight dependent variables (p < .05). The importance between ‘speed’ and ‘dynamics’ was not significantly different, except for the ‘happiness’ emotion (t(19) = 2.95, p < .05). Although the importance of the ‘animation type’ was always biggest among three typographical elements, its relative importance was significantly different among eight measurements (F(7, 133) = 8.27, p < .05). The ‘animation type’ played a relatively less important role in expressing ‘surprise’ (49.01%) and ‘energy’ (45.72%). It was interesting to note that, however, the importance of the ‘dynamics’ element was biggest in expressing these emotions (F(7, 133) = 6.74, p < .05). There was no significant difference in ‘speed’ elements among eight measurements (F(7, 133) = 2.02, p = .57).

Table 1. Relative importance (%) from conjoint analysis. An asterisk indicates significance at p < .05.

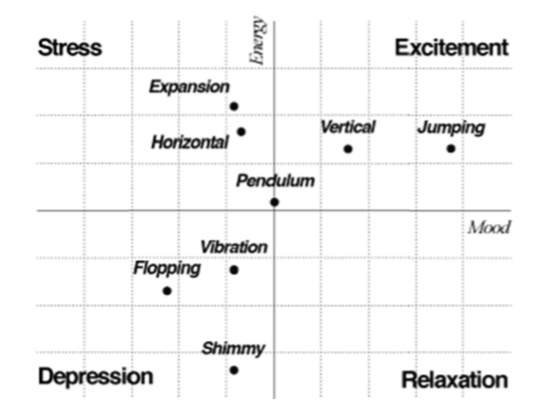

In order to propose the best kinetic typography for each of the six basic emotions, part-worth utilities were derived from conjoint analysis, as shown in Table 2. The post hoc tests indicated that there is no single representative ‘animation type’ for each emotion. Hence, the animation types with a significantly higher utility score were extracted and underlined for each typographical element. Next, we plotted eight animation types on the Affect Grid using the ‘Mood’ and ‘Energy’ scores, as shown in Figure 4. The result from the Affect Grid is qualitatively consistent with the best animation types extracted for six basic emotions. For instance, ‘vertical’ and ‘jumping’ animation types in the excitement (1st) quadrant are suggested for ‘happiness’ or ‘surprise’ emotion. The ‘horizontal’ and ‘expansion’ animations are located in the stress (2nd) quadrant, and they should convey emotions of ‘anger,’ ‘fear,’ or ‘surprise.’ The ‘vibration,’ ‘flopping,’ and ‘shimmy’ animation type were located in the depression (3rd) quadrant, and they should be adequate for ‘sadness,’ ‘anger,’ ‘fear,’ or ‘disappointment.’ For these seven animation types, the changes in speed and dynamics merely act as an ‘amplifier.’ This indicates that the influence of speed and dynamics on the emotional characteristics was marginal.

Table 2.Part worth utilities of each level for eight emotions. The underlined scores indicate a statistical difference at p < .05.

Interestingly, the ‘pendulum’ animation type was plotted on a neutral point. In fact, this received positive utility scores for both ‘happiness’ (0.32) and ‘sadness’ (0.34) emotions. We performed a paired samples t-test between the pendulum type with fast speed and maximum dynamics, and with slow speed and minimum dynamics. The result indicated that the effects of speed and dynamics on the ‘happiness’ (t(19) = -2.57, p < .05) and ‘sadness’ (t(19) = 5.08, p < .05) were significant. This implies that the changes of speed and dynamics function as ‘shunt switches’ when the animation type has a less sensitive emotional stereotype.

Figure 4. Eight animation types plotted on Affect Grid

Discussion and future work

Based on the empirical studies, we suggest a new way of using single-button messengers expecting that they also can deliver the emotions. Firstly, using animated texts with other data can enrich the communication, as shown in Figure 5. For instance, people can send their location on the ‘Yo’ app. Its current function is the notification of the user’s presence, and it is difficult to draw rich communication. On the other hand, location data with animated text connote a much richer communication aspect. People can express their feelings with their presence such as, “It’s really nice to be here,” or “The food at this restaurant tastes really bad.” Other types of data such as health data might also be applicable.

Figure 5. Using animated texts with other data.

Secondly, notification with animated texts can be embedded in the ‘communication with things,’ as shown in Figure 6. Currently, the ‘Yo’ app has been updated with a new function, providing users a new way to subscribe to updates from their favorite online ‘things.’ This shows that the platform has simply outgrown its function and that it is not only for ‘interpersonal’ communication but also communication with ‘things.’ In this situation, animated text can support appropriate notification depending on its contents or users’ preferences. For instance, news notifications about users’ favorite sports teams can be delivered with the excited-feeling animation, or a bad news notification about the stock market can be delivered with a depressed animation. This helps people engage more with the notification.